|

Understanding Capitalism Part III: Wages and Labor Markets

By  - January 11, 2005 - January 11, 2005

We often see "capitalism" defined as a system based on the private

ownership of the means of production.

Capitalism is about much more than this however. One of the major

defining features of capitalist economy is the use of wage-labor and the

existence of labor markets.

Understanding the role of labor markets in capitalism is critical,

and this is best achieved by understanding the historical development of

capitalist economy.

Historical Emergence of Capitalism

Capitalism as we know it today began to emerge as an economic system

in the 1700s, but capitalism as we know it did not become a dominant

force until the 1800s. The first place where modern capitalist economy

developed was in England.

Capitalism grew out of feudalism and mercantilism. During feudal

times production of goods was done primarily at the individual level.

Commodities were produced by individual craftsmen, who were typically

members of guilds. Individuals owned their own means of production.

At this time labor markets were inconsequential in the economy.

People were not generally "employed" to work. People produced

commodities or offered services as workers, but what they were

compensated for was the goods or services directly.

For example, a blacksmith was not employed by a company or group to

make horseshoes at an hourly rate, the blacksmith made tools and

horseshoes and he sold these items directly. He was paid for the

products that he produced. His income was derived from selling his

goods.

Guilds were organizations of workmen, who worked, trained, and often

lived together. Guilds had a number of their own problems, such as

restricting membership and requiring several years of unpaid, or lowly

paid, apprenticeship, however, guilds served as a strong community base

for workers and enforced codes of conduct and standards of quality.

Merchants would go to various independent producers and buy their

goods from them and then trade or sell those goods at a market.

Wage-labor was rare at this point. Merchants didn't control the means

of production, individuals did. The system was not based on the

accumulation of capital. What little wage-labor did exist was typically

regulated by the guilds.

Capitalism really began to emerge after the British Agricultural

Revolution of the 1720s, when advances in agriculture meant that fewer

people were needed to produce food so many peasants were cast off of the

land that they worked. As the feudal system was being ended, previously

communal land began to be privatized and the peasants had no title to

the land so they became homeless and jobless. This was when wage-labor

began to come into more prominent use in the cities, as peasants flooded

the cities looking for work. Shortly after, advances in mechanization

also took place. As this happened the merchant class evolved into the

capitalist class through the building of factories and the employment of

workers to produce products directly for them. It was this accumulation

of capital by entrepreneurs that gave rise to the term capitalism,

though this term did not come into use until the mid 1800s. The

principle characteristic of capitalism is that rights to ownership of

newly created value were seen as coming from ownership of the tools used

to create the value as opposed to the labor used to create the value, as

had traditionally been the view.

The textile industry is one of the important industries in the

development of capitalism.

Pre-capitalist home-based weaver

In the 1700s the textile industry was one of the most important

industries in Britain. The way that textiles were typically made in the

early 1700s was that a family would farm the materials to be used in

making cloth, such as wool or cotton, then they would use their own

spinning wheels and other tools to produce the cloth at home. Special

merchants, called clothiers, would travel from village to village buying

the cloth, which was then sold to tailors and other buyers.

Clothiers making rounds

As you can see, this certainly involved private ownership of the

means of production, yet, this was not a capitalist economy. The people

were not "employed". The people did not work for anyone else (well

technically they worked for the king). The concentration of capital was

not the modus operandi of industry. People lived and worked at home,

they produced goods, and their "income" was a product, directly, of the

goods that they produced. Individuals owned and controlled their own

means of production and thus they owned the products of their own labor.

In 1764 the Spinning Jenny was invented, and this labor saving device

enabled spinners to produce thread more quickly. At that time a few

merchants began setting up their own small "factory" type establishments

and employing small groups of women to produce thread for them, but this

was still a rare situation.

Spinning Jenny

In 1771 Richard Arkwright setup the first true factory system, which

used spinning machines operated by a water driven wheel. These textile

factories employed large numbers of people, mostly children. Two thirds

of Arkwright's "employees" were children, and Arkwright employed

children as young as 6 years old. Arkwright built cottages next to his

factories where displaced peasants came to live and work for him, and he

specifically preferred large families with many young children. These

peasants had no property and no money and so were willing to work for

Arkwright and put their children to work in the factory in order to

avoid starvation.

This, effectively, can be viewed as the beginning of modern

capitalism.

Arkwright's system proved so productive that the independent home

producers were no longer able to compete, and were driven to give up

their independent work at home in the villages to move to the cities and

work in factories. Arkwright became so successful that within a

relatively short period of time he was able to fix the price of cotton

twists, to which all other makers conformed.

Even at this point, though, wage-labor was not a widespread

condition, it was still in its infancy. Over time, however, industry

after industry moved from the old ways of independent production by

individuals, craftsmen, and guilds, to the collective production of

wage-labor capitalism.

The independent means were of course less efficient, and it was the

increases in efficiency, which the capitalists embraced and promoted,

that forced individuals to give up their independence to work for wages,

which were typically lower than their previous incomes.

This is important to understand, because capitalism is not just about

private ownership of the means of production, indeed it is about the

private ownership of the means of production, the private concentration

of capital, and the employment of wage-labor.

The result of capitalism is that labor went from being seen as the

source of property rights to being a commodity, and instead capital

ownership became seen as the source of rights to newly created property.

With the capitalist system, labor is a commodity, no different than

raw materials. It's one more thing that capitalists factor into their

budget as a part of the cost of production.

Just like other raw materials, the price of labor becomes market

driven.

The Meaning of Labor Markets

Under the capitalist system workers are no longer paid for the value

of what they produce, nor do they retain rights to ownership of what

they produce, instead they are paid by how little compensation someone

else is willing to do the same job for. Just as it is understood that

market competition drives the price of other commodities down, it has

the same impact on labor when labor is a commodity.

Labor markets and other commodity markets are two separate and

distinct markets. By separating the cost of labor from the value of

labor, capitalists are able to increase profits. Profits are generated

in part by the difference between the cost of labor and the value that

the labor has created, as Adam Smith himself stated.

Though the manufacturer has his wages advanced to him by his

master, he, in reality, costs him no expense, the value of those

wages being generally restored, together with a profit, in the

improved value of the subject upon which his labor is bestowed.

- Adam Smith; The Wealth of Nations

By having separate markets the demand for jobs creates different

pricing on labor than the demand for goods and services creates on the

products of labor.

It separates people from the value of what they produce, so no matter

how much value a worker creates, their wages are governed by the labor

market, not what they produce. With two different markets the criterion

for compensation is completely changed. Wage-laborers don't receive the

"fruits of their labor" - instead they are paid by "job performance".

Job performance is judged, not in relation to the product of the

worker's labor, but in relation to other workers in the market. Thus,

under the capitalist system, workers' incomes become socialized.

This is important for understanding how corporations work today. One

way to describe a corporation is as an organization of individuals.

All employees of a corporation are wage-laborers, even the CEO,

although executives also typically get part ownership in the corporation

via shares of stock and they have control over the corporation. CEOs

play the role of both capitalists and wage-laborers. Most employees,

however, are just wage-laborers.

The way that corporate wage-labor works is that all of the employees

work together as a team to create value. It becomes virtually impossible

to determine exactly how much value each individual contributes to the

sum total of value created by the corporation however and workers do not

retail ownership rights to the products of their labor.

There is absolutely nothing in capitalist (neoclassical) economic

theory that even attempts to compensate employees by the "real"

contribution made. Capitalist economic theory dictates that wages are

determined by labor markets, so how much each employee gets paid is not

determined by their contribution, but rather by the market value of

their labor. There is no way to determine who is really responsible for

the value created. The market value of each employee's labor is

determined basically by how much other people in the market are willing

to sell their labor for.

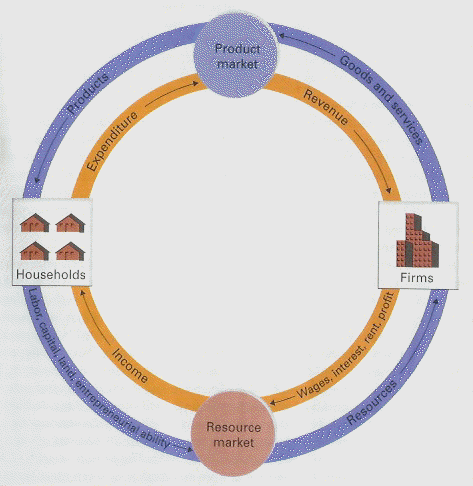

This is illustrated by the following diagram taken from a college

level economics textbook, Economics 6e The Wall Street Journal

Edition, by William McEachern, 2003.

This highly simplified model illustrates that the labor market

(resource market) is completely separated from the product market.

Determining the real "value-added" of each employee is more difficult

than simply paying market wages, but what paying market wages also does,

is make it much easier to take advantage of employees. This makes

redistribution of value within the corporation much easier, and is

indeed a major factor in contributing to executive compensation.

The salaries of corporate executives have grown by a factor of more

than 10 over the past 20 years. In 1980 the average corporate executive

was paid about 42 times the salary of the average employee. In 2000 that

figure had increased to 500 times the compensation of the average

employee.

http://www.faireconomy.org/research/CEO_Pay_charts.html

Commenting on this turn of events, William J. McDonough, chairman of

the New York Federal Reserve Bank, said, "I find nothing in economic

theory that justifies this development, I am old enough to have known

both the CEOs of 20 years ago and those of today. I can assure you that

we CEOs of today are not 10 times better than those of 20 years ago."

See: Fed official decries CEO salaries

Ironically, there is something in economic theory that does explain

this development, it is as I have discussed: Compensation is not based

on contribution, it's based on the labor market.

Executive compensation has gone up, not because executives of today

are contributing 10 times more value to their corporations, but because

the average worker for these corporations is receiving a smaller share

of the value that they contribute, and this of course includes foreign

workers as well. This allows compensation for those at the top to

increase.

We can use an example to demonstrate how wages can work in relation

to value production. Money won't be used in this example, instead the

material goods that are represented by money will be used directly.

Let's say that Jim works for a company that makes widgets. The

company he works for has 10 employees: a secretary, a janitor, a general

manager, a shop foreman, two salesmen, and four widget makers.

Jim is a widget maker at the production facility where he makes 75

widgets a day, for sake of argument we will assume that he takes a raw

piece of metal and turns it into a completed widget using the tools

provided to him by the company.

Of the ten people working at the company the widget makers are the

only ones who actually produce a tangible product.

Let's break it all down into weekly production and compensation.

Assuming that all four widget makers make 75 widgets a day, that is

1,500 widgets a week.

The 1,500 widgets are owned by the "corporation". As Jim makes his

widgets they go into the common stock of the company, out of which all

of the employees are compensated.

At the end of every week they open up the company vault and dole out

the widgets to the employees for compensation. Off the top, 500 widgets

are used to pay for non-labor expenses, such as rent and other bills.

The secretary takes home 30 widgets a week. The janitor is paid 20

widgets a week. The salesmen are paid 85 widgets a week each. Two widget

makers take home 50 widgets each, another takes home 55 because he's

been there a while, and Jim takes home 60 because the boss likes him.

The foreman gets 100, and the general manager is paid 165. That comes to

700 widgets. The remaining 300 widgets a week are "profits" that go to

the company, either for reinvestment or to be realized by the owner.

Of course, in real life, all of the widgets are sold in exchange for

money and the money is used to pay the employees and the owner. It's

important to remember, though, what that money represents and the

underlying "mechanics" of the system. The money represents the widgets

that were created and sold by the employees.

Fundamentally, the example demonstrates what is "really" going on.

So, how is it that the secretary's pay is determined to be 30 widgets a

week? Simply by "the market", by what other people are willing to do the

same work for.

Why is Jim paid 60 widgets a week? For the same reasons sort of, but

he also gets a little more than market price (50 widgets)

because "the boss likes him". However, Jim, and all the other widget

makers, are really all producing 375 widgets a week. He's actually

making 375 a week, but he only gets to keep 60 of them. To put it in

other terms: he is producing 375 widgets a week but he is only receiving

the value of 60 widgets a week.

The manager is getting 165 widgets a week out of the 1,500 widget a

week production capacity.

Obviously all the people involved play some role in the production of

the 1,500 widgets each week. As a team they all work together to

facilitate this production. In the example provided they all seem to be

compensated on a relatively equitable basis.

One can argue that each person's "pay" represents the value of their

contribution to the production of the widgets, but this is not the way

that our system works. That is certainly an approach that

could be taken, but this is not the approach that is

taken in the capitalist system.

Again, labor markets determine compensation. Instead of

trying to figure out what exactly is the value that a given worker

contributes, the labor market determines the "price of labor" via

competition in the marketplace.

It's much easier to see the difference if one considers a business

partnership.

When two people enter into a business partnership, they will agree

among themselves on the relative compensation for their efforts. For

example, if Jim and Bob enter into a partnership where Jim provides most

of the manual labor by creating products, and Bob acts as the salesman

and financier, then they may agree to a 50/50 split of the "profits".

Now, as time goes on, if one partner or another feels that he is

doing more than 50% of the work then he will be inclined to discuss this

with the other partner and discuss changing the levels of compensation

or getting the other person to work harder, etc.

For example, if Jim works 6 days a week for 9 hours a day in a

machine shop producing high quality parts, and his partner Bob spends an

hour or so a day making business calls from his cell phone, then Jim may

reevaluate the relative contributions that they are making and start a

conversation to ask for a larger share of the profits, or to ask Bob to

do more work if he wants to earn his share.

This type of evaluation and economic decision-making is not based on

market theory and, indeed, neither one of the partners are

"wage-laborers" in this relationship, they are partners in an

enterprise. They are both enfranchised within the construct of their

business relationship. The members in the partnership evaluate the

justice of their compensation not on market principles, but on the

perceived value of their relative contributions.

This type of evaluation is an attempt, by the parties involved, to

match compensation with contribution.

This difference in types of compensation, market determined vs.

contribution determined, is critical to understanding capitalism.

What capitalists try to do is promote competition in the labor

markets and limit competition in the commodity markets, which of course

is why industry is opposed to collective bargaining. Today's

neoclassical economic view simply calls this "good business practice",

or "entrepreneurial ability".

An important method of increasing the discrepancy between labor

markets and commodity markets is the fragmentation of labor markets

across trading boundaries and regions, such as between nations and

across currency boundaries.

Capitalists seek to maintain the ability to hire wage laborers across

boarders, while limiting markets within boarders. In this way consumer

markets are more restricted than labor markets, leading to relatively

higher prices for goods at a lower cost of labor to produce those goods.

For example, at present it is relatively difficult for American

consumers to buy goods in Mexico, Canada, or China, but it is relatively

easy for employers to hire workers in Mexico, Canada, and China. This

limits the commodities markets, while expanding the labor market,

allowing for higher profits by corporations by enabling them to keep a

larger portion of the value that workers create.

This is really what so-called post-modern "free trade" is all about.

Free trade, as it was initially envisioned by men like John Locke and

Adam Smith, was about the freedom of merchants to exchange goods with

merchants in other regions that had commodities and raw materials that

were not available locally, without having to pay taxes and tariffs to

kings just to be able to do business.

It must be remembered that wage labor was virtually non-existent when

John Locke wrote about free trade and it was rare when Adam Smith wrote

The Wealth of Nations. What these men wrote about was the trading

of goods and raw materials because some regions of the planet simply

didn't have things that other regions did have.

Today, however, what is really being traded is not goods, but labor.

American companies mainly want "free trade" with other countries, not

because they have things that we don't have, but because they want

access to "cheaper labor". It's not just about gaining access to "cheap

labor", however, it is also about labor market fragmentation and the

separation of labor markets from commodity markets.

By creating a labor market that is unified for capitalists but

fragmented among workers, workers are put in competition with other

workers all over the world. While American workers are in competition

with Chinese workers who may get paid 30 cents an hour to make Nike

shoes, Americans cannot buy Nike shoes at Chinese prices, because our

commodity market is restricted to America for the most part, where those

shoes sell for an average of about $40 a pair.

Nike factory in China

Unfortunately, on top of inherent tendencies of labor markets to

under-compensate many laborers, the Chinese government suppresses the

price of labor as well. In 2004 the AFL-CIO released a report detailing

the repression of workers' rights in China. In this report they

concluded that the activities of the Chinese government are responsible

for lowering the wages of Chinese workers by 47 to 86 percent. Among the

criticisms of Chinese working conditions cited by the report are the

inability of Chinese workers to form unions (they can only be members of

the official state union, which actually does more to work against the

rights of workers than for them), the lack of safe working conditions,

the lack of enforced minimum wage, and the use of forced labor.

See: AFL-CIO Petition on China's Denial of Workers' Rights

At the same time, the US now has the largest trade deficit with China

of any country. In fact, we are one of the few countries trading with

China to have a deficit.

This, of course, puts American workers into a global labor market

where we are in competition with workers who are deprived of what we

consider to be fundamental human rights. American capitalists have

profited highly from this situation, eager to use the labor of Chinese

workers, who exist in a highly depressed labor market, to produce goods

that can be sold in America in our relatively inflated commodity market.

The Chinese workers, of course, do not own any of the value that they

produce, and are not compensated at a rate even close to the value of

the products of their labor. That is why American corporations are able

to realize such high profits from the use of Chinese labor.

The globalization of labor markets inherently benefits capitalists

because consumers will never have access to a global commodity market.

While consumers are increasingly able to buy from overseas directly,

this pales in comparison to the ability of producers to engage in global

employment. There will always be some degree of restriction for

purchasers when buying products. As a buyer, I cannot "shop" in China

tonight for my next pair of shoes, I will shop either at a local store,

or on-line through a legal retailer, who will impose upon me the same

basic market restrictions that local physical locations impose. My

access to the Chinese market directly, as a consumer, is effectively

illegal unless I physically travel to China, and then all manner of

restrictions would still be placed on me if I tried to import a large

amount of goods back to America.

So, my access to Chinese-made goods, directly at Chinese prices, is

virtually impossible as an American consumer, but American capitalists

do not have these restrictions and in fact work through the American

government to ensure that there is an imbalance of restriction placed on

consumers so that American consumers can only get access to products

through "official" avenues of trade. The "unofficial" avenue of trade is

of course called the "black" market, or, in real terms, the only true

"free market" that exists for commodities.

Conclusion

What really makes capitalism capitalism is that ownership rights to

newly created value are based on ownership of the tools used in the

production of value, not the labor used to create value. Labor is not

seen as the source of property rights, capital ownership is. The result

is the private concentration of capital and the widespread adoption of

wage-labor, resulting in the dominance of labor markets as the

determining factor in labor compensation. Labor markets do not, in any

way, guarantee that worker compensation is comparable to the value that

workers produce.

Within the context of a business partnership, partners share

ownership and are much more likely to accurately access their relative

contributions and be compensated in a way that accurately reflects the

productive value of the labor that they contribute to the business.

If a real attempt at fairness in an industrial economy were made,

then at the very least workers would be informed of the financial

records of the company they were applying to work for, the pay of all of

the workers in the company, the value of the goods and services made by

the company, the rate of profit on these goods and services, and a cost

benefit analysis for the position that they are applying for.

In other words, workers would be treated like partners.

Instead, of course, our work lives are shrouded in mystery and

secrecy. Numbers are kept from virtually everyone, and in many cases

even asking fellow employees what their salary is can be grounds for

dismissal. Not only do labor markets not guarantee just compensation for

work done, but our labor markets are extremely flawed on top of that, in

ways that act against the interests of wage-laborers. Market theory is

fundamentally based on actors in the market being fully informed, and

what we can certainly say is that the majority of wage-laborers are very

poorly informed about the full value of their contributions to their

employers.

The purpose of hiring an employee is for that employee to generate

value for the employer. Every employer is making a profit from the work

of their employees in theory. In order for an employer to run a profit

then their employees as a whole have to be creating more value than what

they are compensated.

Though the manufacturer has his wages advanced to him by his

master, he, in reality, costs him no expense, the value of those

wages being generally restored, together with a profit, in the

improved value of the subject upon which his labor is bestowed.

- Adam Smith; The Wealth of Nations

The question for wage-laborers is: "How much is my employer making

off me?" That is a very legitimate question, and one that every

worker should be able to answer. It is only when every worker can answer

that question, and be comfortable with the answer, that

economic justice can be discussed as a part of the capitalist system.

Understanding Capitalism Part I- Capital and Society

Understanding Capitalism Part II- Personal Property, Money and

Finance

Understanding Capitalism Part IV- Capitalism and Culture

|