|

The Case for a National Individual Investment

Program

By

- July 10, 2014

- July 10, 2014

First off, what is a "National Individual Investment Program"? At its

most basic, a National Individual Investment Program is a means of

distributing ownership of capital assets more equally among all citizens.

A National Individual Investment Program would not

fundamentally change anything about the American system of ownership, it

would simply ensure a more equal distribution of ownership among

individuals. Capital would still be privately owned the same way it is in

America today, it's just that all citizens would own meaningful amounts of

capital. Importantly, a National Individual Investment Program would not

only ensure that individuals retained ownership of capital, it would

actually reduce the roll of government in the economy by reducing the need

for government-run social safety net programs.

Today the richest 10% of Americans own over 80% of stock market assets,

while the poorest 90% own less than 20% of stock market assets. A National

Individual Investment Program like I am proposing would simply result in a

much more even distribution of asset ownership, without directly changing the

American economic system. Thus, after several decades of implementation, instead of the richest 10% of

Americans owning 80% of stock value, the richest 10% may own 30% of stock

market value, while the poorest 90% own 70% of the market.

The stock market certainly does not represent the entirety of capital

assets in America, but it is a large and important segment of capital

assets. It is also a segment of capital assets that is relatively easy to

distribute among the population due to the nature of the assets. Other forms

of capital include financial securities such a bonds, direct business

ownership, and commercial real estate. Of these, bonds would also be

included as a part of the National Individual Investment Program since the

bond market is similar to the stock market in ability to distribute the assets.

Ownership of commercial real estate and private businesses (which are the

majority of businesses in the country) would not be impacted by the program.

The proposed National Individual Investment Program would do nothing to

increase the distribution of ownership of those forms of capital, but just

addressing stock and bond market ownership alone would have a significant

impact on the American economy, provide greatly improved economic security

for millions of Americans, and would likely have profound impacts on our

democracy.

How exactly would such a program work?

The exact details of such a program could be tweaked in a number of

different ways, but the basic structure of such a program would be the

following:

Shares in total stock market and bond market index

funds would be distributed to virtually everyone in the country on an

on-going basis. The shares would be paid for via a dedicated income

tax, similar to the current Social Security tax. The tax would be a defined

flat tax of roughly 8% on all income, with the first $30,000 of income, and

government benefits (like Social Security), being exempt.

Shares would primarily be paid out based on the number of hours an

individual worked, with a cap of 2,080 hours a year (40 hours a week over 52

weeks). The cap would be applied on a yearly basis so that those who work

overtime in seasonal jobs would not be unduly penalized. Salaried employees

would be counted as working 40 hours a week. In addition, shares would be

distributed to people with disabilities (of working age), when people graduate high school,

and when citizens obtain a Social Security number, which is typically when a

they are born. Another consideration would be to provide benefits for

stay-at-home parents as well. Under this scenario a full-time working

parent, a part-time working parent or a parent with no paid job would all

receive the same benefit, under certain defined conditions.

Prior to turning 18 years old the shares would be held in trust and could not be

accessed by you or your parents. Once you turn 18 the shares would be yours

to do with as you wish and would be treated like shares in a normal mutual

fund. All new shares would have a one year vesting period when they could

not be sold or transferred. The national whole-market index funds would be held and managed by the

federal government in order to reduce the costs of administration. The index funds would pay out a dividend based on the market,

like a normal fund. Income from dividends or the sale of shares would be

normal taxable events. Individuals would be allowed to transfer their shares

to accounts held at private institutions if they wished once they are vested, and would be

allowed to exchange them for qualifying private mutual funds, money

market accounts, etc., as non-taxable events.

While the administration of the program would be similar to Social

Security in some ways, there would be important distinctions as well.

Firstly, this would not be a retirement program. Adults would have direct

access to their assets, just like any normal private investment. Secondly,

individuals would actually own the assets, which is really the entire point

of the program, to ensure distributed ownership of capital assets. Thirdly,

and very importantly, unlike Social Security, there would never be any

"trust fund" and the benefit would never be defined. The way that Social

Security works is that the benefit is defined up front, and then taxes are

levied in order to meet that funding obligation. This would work in the

opposite way. The tax would be defined up front, and however much revenue is

collected via the tax is what would get paid out. When the economy does well

and collections increase, then everyone's payout would increase. When the

economy does poorly and collections go down, then the payouts would go down.

The program would never run either a surplus or a deficit, it would be a

straight money-in-money-out program.

The program is not intended to replace or diminish Social Security

however. The fact that Social Security works differently is not a bad thing,

it is a very good thing, which provides economic stability and

diversification. Having multiple different programs that work in different

ways helps to create economic stability and security under a variety of

economic conditions.

A program such as this would result in a far more equal distribution of

financial asset ownership over the long-term, without short-term shocks to

the current system.

Under such a program, given the gross national income of $16 trillion in

2012, roughly $11 trillion in income would have been subject to the 8% tax,

resulting in approximately $880 billion being raised by the program. If we

assume a 1% administrative cost (a little more than the administrative cost

of Social Security), that leaves about $870 billion which would be paid out

to citizens. If we assume that 75% of the 313 million people in America

would receive full benefits, that would have resulted in an average

full-time worker benefit of $3,700 worth of assets in 2012.

This means that a full-time fast food worker that was paid minimum wage

would have paid nothing in National Individual Investment Program taxes,

because their entire income was under the $30,000 exemption, but they would

have received $3,700 in investment assets. At the same time a salaried CEO

with a total income of $10 million would have paid $797,600 in National

Individual Investment Program taxes and received the same $3,700 in

benefits. This would create a break-even point of around $75,000 in total

income. Full-time workers with incomes below $75,000 a year would receive

more in benefits than they paid in taxes, while individuals with incomes

over $75,000 would pay more in taxes than they received in benefits.

The primary reason to make distribution of the shares largely contingent

on working hours is to increase public support for the program by ensuring

that the benefits are perceived as "earned". Provisions for other means of

receiving shares, such as disability and parenting, would be important means of insuring

broader distribution and inclusion of some of the most needy populations. A

case could also be made to remove the work provision and simply grant the

shares to all working-age adults, regardless of work status. I believe the

program would have stronger public support with the work provision however.

Assuming a distribution of $3,700 in 2012 for a newborn child upon

receipt of their Social Security number, and a modest average annual rate of

return of 5%, a child born in 2012 would have nearly $9,000 in assets in

their National Individual Investment Program account upon turning 18 even if

they received no additional distributions. If the average child began

working part time at age 16 and graduated high school, they could easily

have over $15,000 in assets by the time they graduate high school.

An individual who graduated high school with $15,000 in assets and who

received an average of roughly $3,000 in assets a year would have around

$125,000 in assets from the program by age 40 if they never sold any of

their assets, from which they would be

getting around $2,500 a year in dividends assuming a modest 2% dividend.

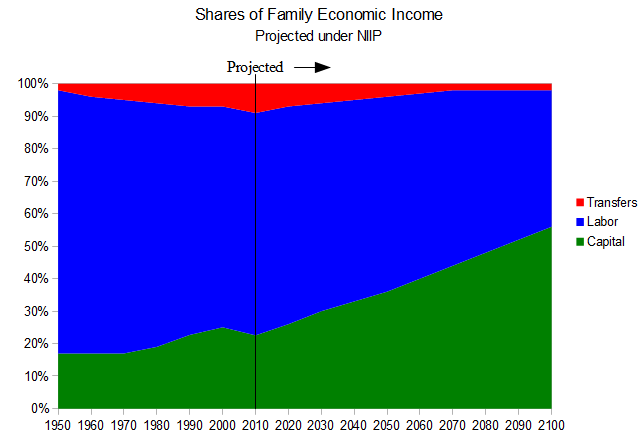

Over time, if and when the portion of national income going to capital

increases and demand for labor decreases, the size of the tax could be

adjusted and the number of working hours required to receive full benefits

could be reduced. If demand for labor declines, then the definition of a

"full time" employee should be reduced, allowing individuals to collect the

maximum benefit through fewer working hours.

Why would we want such a program?

There

are multiple reasons, ranging from the practical to the philosophical. First

let's start with the practical reasons.

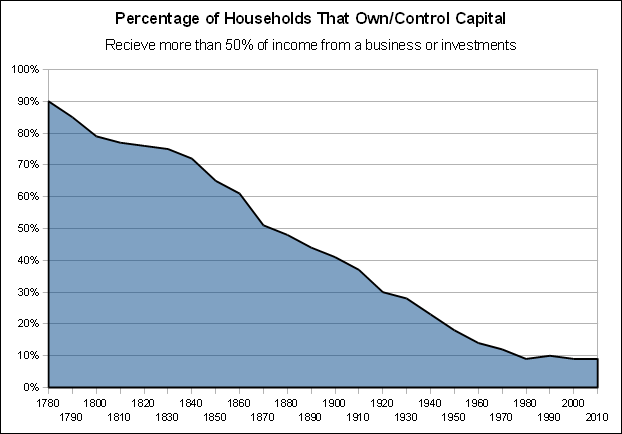

Capital ownership has become increasingly concentrated

throughout American history. When the country was founded roughly 90% of

citizen families owned meaningful capital from which they derived income,

primarily land.

Today less than 10% of American families own meaningful capital from which

they derive income prior to retirement.

This concentration of capital

ownership is an inherent product of industrialization and capitalism, but it

has also been facilitated by government policies over the years as well.

As reported by the

Washington Post

in 2011, "Over the past 20 years, more than 80

percent of the capital gains income realized in the United States has gone

to 5 percent of the people; about half of all the capital gains have gone to

the wealthiest 0.1 percent."

Share of capital income received by top 1% and bottom 80%, 1979-2003

source:

Unnoticed CBO Data Show Capital Income Has

Become Much More Concentrated At The Top, 2006

http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html

http://www.cbpp.org/files/1-29-06tax2.pdf

Today, despite the fact that a larger portion of the population owns

investment assets such as stocks than in the past, actual capital income is

increasingly going to a smaller portion of the population. There are a

variety of reasons for this, ranging from tax policy to the fact that while the number of

people owning at least one share of stock has increased over the years, the

actual value of the assets held by the bottom 90% of the population has

declined. Think of all capital income like a pie. Over the past 40 years the

size of the pie slice owned by the bottom 90% of the population has shrunk,

while more people among the bottom 90% are getting a piece of that slice. In

other words, the slice is being shared more broadly, but everyone is getting

a smaller piece. On the other hand, the slice of pie going to the top 1% has

gotten larger.

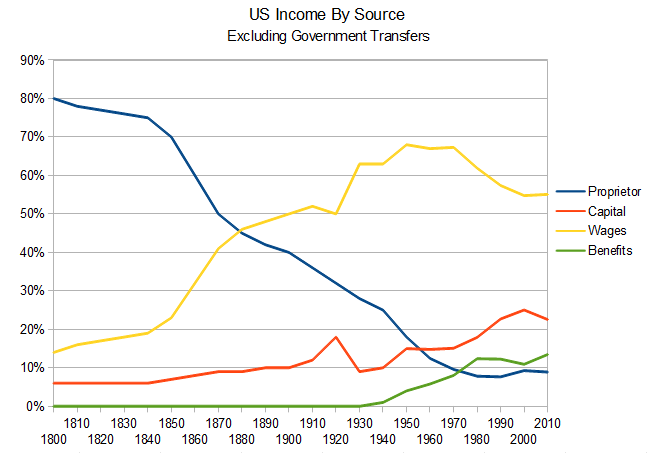

The other important fact that is often overlooked is the fact that over

that past 100 years the portion of the population directly owning their own

capital has declined at a pace that exceeds the rate of financial asset

acquisition. In other words, 100 years ago a far greater portion of people owned their own

business and worked for themselves or within a family owned business. The

largest portion of these people were farmers who owned their own land and

equipment. As small businesses were overtaken by larger corporations, more

people became wage-laborers. Some of these people acquired stock or other

financial assets, but the acquisition of financial assets has not offset the

decline of directly owned capital assets by individuals over time. Even

today, the majority of self-employed people have no meaningful capital

assets. The majority of the self-employed today are primarily selling their

labor, as consultants, contractors or service workers.

The reality is that an ever increasing share of national income in

America is going to capital, while the percentage of national income going

to wages has been steadily declining from its peak after World War II.

So while an increasing share of capital income has been going to the

wealthiest Americans over the past several decades, the portion of national

income going to capital has been increasing as well. Thus, the wealthy are

getting an increasingly larger share of a growing pie, while the bottom 90%

are getting a declining share of the growing capital pie, in addition to a

declining share of a shrinking wage pie.

There are numerous causes for this phenomenon, ranging from the

off-shoring of manufacturing to trade policy to the decline of unions to tax

policy to demographics to increasing automation to concentration of capital

ownership and more; but ultimately the point is that wages are currently the

primary means of distributing income to the majority of the population, and

wages are a declining component of national income. There are essentially

three groups of people who don't rely on wages as their primary source of

income: retired people, those living in poverty, and the very rich. The

primary sources of income for retired people are pensions, personal

savings, and Social Security. The primary source of income for those living

in deep poverty is transfers from the government, while those in moderate or

temporary poverty may rely on a mix of wages and government transfers. The

primary source of income for the very rich is capital income. Roughly 75% of

the incomes of the richest 400 Americans comes from capital gains and

dividends, and even without income they have significant accumulated wealth

that makes the need for actual income superfluous. For example Bill Gates'

current estimated wealth is $72 billion at age 58, which means that even

with no new income for the rest of his life he could easily spend over $2

billion a year and not run out of money before he dies.

So the issue is that virtually all households require income, and ever

since industrialization wages have been the primary means of distributing

income among the population. Prior to industrialization individual capital

ownership and self-employment were the primary sources of income in America.

Today, however, we have a situation where a growing portion of the

population is dependent on wages for income, while the portion of national

income going to wages is declining. This, of course, is a fundamentally

unsustainable situation, and it is one that individuals can really do

nothing to change. The best that any given individual can hope for is to

become one of the few people who are able to acquire a large amount of

capital, but fundamentally, given our current system, it is impossible for

everyone, or even significant numbers of people, to do that. Our system

works fundamentally like a lottery. It isn't based purely on chance like a

lottery, but it is like a lottery in the sense that we have a few big

"winners" with a large number of people contributing to the pool that makes

those large "wins" possible, and it is impossible for everyone to "be a

winner", no matter how hard everyone works or contributes. Even if the

country were populated with nothing but 300 million Bill Gates clones, only

a few would be rich and many would live in poverty. That is a fundamental

function of our economic system.

There are basically three ways to address this situation with a goal of

reducing economic inequality. One is to try and increase the share of

national income going to wages, thereby reducing the portion going to

capital. This would presumably be done by increasing wages through things

like minimum wage legislation and unionization. Another option is allow

the share of income going to capital to continue to increase, but ensure

that capital income is broadly distributed, thereby increasing the share of

capital income going to the bottom 90% of the population. Both of those

approaches address income at the source. The third option is to allow

before-tax income inequality to continue to rise, but use taxation and

government transfers to re-distribute that income through various programs.

The conventional approaches employed in America have been

to pursue the first and third options. This is basically what the New

Deal did, and it did work to a large extent. The most fundamental problem

with this approach, however, is that it did nothing to address the

underlying concentration of capital ownership and financial power. Thus, as capital ownership continued to be consolidated the ability and desire

of capital owners to

undermine those approaches increased. The

problem with the first and third options is that they address the symptoms

of income inequality without addressing the root cause. Both of these

approaches seek to alter income distributions while leaving in place the power

structure that creates highly unequal income distributions to begin with. Leaving

that power structure in place, concentrated ownership of capital, inevitably

ensures an on-going desire and source of power to undermine any policies

that seek to reduce income inequality.

In addition, both the first and third approaches create friction against

increasing economic efficiency. Attempting to increase total wages

undermines the progress of automation, and essentially relies on preserving

or increasing inefficiency as a means of distributing income. Allowing before-tax income

inequality to rise and relying on government transfers to reduce income

inequality after the fact has numerous inherent problems, ranging from

growing bureaucratic inefficiency to the on-going political peril of any

such programs as taxes would increasingly fall on a smaller and smaller

portion of the population and redistribute larger and larger amounts to the

rest.

From a practical macro-economic standpoint, the reliance of our economy

on wages as the primary means of distributing income to the majority of

people is a barrier to economic growth and efficiency, and locks the

population into working as a means of survival. We are reaching a

point technologically where more and more work can be automated. That

automation is performed by machines, which are a form of capital typically

built by wage-laborers and owned by

investors. This contributes to the decline of wages and the increase of

capital income. But if increasing automation and efficiency results in

declining wages, and as a result declining incomes for 90% to 95% of the

population, then automation will inherently undermine the economy because it

will decrease the wealth of the majority of the population. This means that

increasing productive efficiency becomes counter productive at a

macro-economic level. This condition has been predicted for a long time,

over 100 years in fact. In a sense it is similar to predictions of

over-population and peak oil. It is something that logically will definitely

happen at some point, the issue is determining when that point will be. Just because people have been predicting that it will happen "soon" for a

long time without it happening doesn't mean that it will never happen, just

as, logically, the earth will run out of naturally occurring oil at some

point. People who thought it would happen in the 1990s were wrong, we didn't

run out of oil or even hit peak oil in the 1990s, but inevitably it will

happen some time.

The same issue exists with production efficiency and "job creation".

While it's true that increasing efficiency during the early part of the

industrial revolution resulted in net increases in worker demand, there is

some point at which automation and increasing efficiency will result in net

decreases in worker demand. Whether we are at that point now or not doesn't

change the fact that we should be preparing the economy for this

eventuality. The other major cause of decreasing domestic labor demand is

off-shoring. Distributing capital ownership relatively equally among the

domestic population protects the domestic economy from the effects of both

automation and off-shoring. A more equal distribution of capital ownership

ensures that increases in economic efficiency benefit the entire population,

and thus the overall economy. In other

words, once individuals actually own capital, the dependence upon government

programs and labor laws is diminished. The reason that we need wage laws and

income assistance programs today is that a tiny fraction of the population

owns almost all of the capital, and the vast majority of people are

disenfranchised of capital ownership. This dichotomy is what creates the

need for all of these other mechanisms which attempt to rectify the

economic problems caused by highly unequal capital ownership. The reason why

there has been an increased need for these types of programs and regulations

over the decades is because ownership of capital has become increasingly

concentrated. But instead of trying to maintain or increase labor's share of

income, as has been the traditional approach of the labor movement in

Western countries since the industrial revolution, we should instead be

trying to increase the working class' share of capital ownership, and

allowing the share of income going to labor to decline, as depicted below.

Not only does the concentration of capital ownership create economic

problems in terms of income distribution, but it is also the root source of

disproportionate political power which undermines democracy, and further

thwarts economic reforms. This is why the New Deal has ultimately failed,

because it sought to address the issue of income distribution without

addressing the issue of capital ownership distribution. Thus the New Deal

did not address the concentration of political power that resulted from

concentrated capital ownership, which has ultimately been used to undermine

the New Deal reforms. Under New Deal type policies, economic fairness and

moderated income inequality exist only at the discretion of the law. When

capital ownership is distributed then economic fairness and moderated income

inequality are inherent qualities of the system. Right now, because of

highly unequal capital ownership, the economic system is inherently highly

unequal, and we implement laws that attempt to rectify the inequalities

caused by highly unequal capital ownership. These polices are always in

peril because they can exist only at the discretion of the capital owners,

who have disproportionate political power. That's why capital ownership itself must be highly

distributed, so that the political power that comes from capital ownership

is also highly distributed instead of remaining concentrated, as it did

under New Deal era policies. The distribution of capital ownership to the

broad population, as was originally done when America was founded through

land distribution policies, is what will ultimately protect the economic

interests of the broad population. Not only does distributing capital

ownership ensure distributed capital income, but it also ensures the

distribution of political power necessary to preserve that distribution of

income. That's why the New Deal failed, because it did not ensure the

distribution of political power necessary to protect "itself". This is also

why the various "Communist" revolutions of the 20th century resulted in

abuse of power and repressive systems, because those revolutions too

resulted in concentration of capital ownership in the hands of the state.

This is what makes highly distributed ownership of capital among the

citizens so important. Ownership of capital is the source of political

power; distributed capital ownership results in distributed political power.

The distribution of political and economic power that resulted from

America's early land distribution policies was a critical factor in

America's early political and economic success.

Philosophical Justification

Not only does increasing the distribution of capital ownership, thereby

increasing the distribution of capital income, make sense from a practical

perspective, it makes just as much sense from a philosophical perspective.

To understand some of the philosophical justifications for this type of

capital distribution we can go back to the Enlightenment thinkers whose

ideas laid the foundation for America's political and economic systems.

We first have to begin with the fundamental

concept of "private property". While there are many positive aspects to the

concept of private property, such as ensuring that individuals reap the

benefits of value that they create, there are negative aspects of private

property as well. We first have to understand that "private property" is a

social construct, it isn't natural. The existence of private property is

predicated on social agreement. Naturally, everything is common property,

i.e. belongs to no one / everyone. In 1690 John Locke famously laid out the

philosophical justification for private property, in his argument against

the existing aristocratic system of royal property ownership, in his

Second Treatise on Civil Government.

Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet

every man has a "property" in his own "person." This nobody has any

right to but himself. The "labour" of his body and the "work" of his

hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of

the state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his

labour with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby

makes it his property. It being by him removed from the common state

Nature placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it that

excludes the common right of other men. For this "labour" being the

unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right

to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as

good left in common for others.

In all of Locke's discussion on private property, he deals solely with

the creation of private property from public property, or "non-property".

Everything that Locke talks about regarding property in his Second Treaties

deals with an individual applying their labor to unclaimed resources, and

how the application of their labor justifies defining the objects that their

labor is applied to as their private property. While I think virtually

everyone would agree with Locke's arguments, they are unfortunately too

simplistic.

Locke also notes that these rules should only apply when "there is

enough" and there is property "left in common for others". These are

hugely important caveats, which Locke unfortunately doesn't go on to

significantly address. What do we do when there isn't "enough" and there is

no property "left in common for others"? Locke doesn't make it clear, but he

does make it clear that at the very least, the rules of private property

that he laid out shouldn't apply.

Unfortunately, almost everyone today thinks about private property in the

terms that John Locke laid out, but fails to deal with all of the ways that

reality violates the principles laid out by Locke. This leads to a belief

that the property that people own is all acquired via the methods laid out

by Locke, when in fact almost no property is acquired that way in modern

societies. Thus much, perhaps even most, private property ownership in

modern societies is not justifiable according to Locke's principles.

This is because there is very little property "left in common". Private

property ownership creates a paradox, which Locke did not address. While

defining private property apart from common property upon the application of

one's labor is eminently justifiable, once that private property is defined

it now inherently disenfranchises others. Locke dealt with this fact via his

simple caveat that the rules of private property should only apply when

there is "good left in common for others". As long as there is plenty of

property left in common for other people to acquire then the paradox of

private property is unimportant, but as soon as there is not sufficient

property left in common then it is a problem.

Let's use some examples. Let's say that a group of people settle an area,

and the first settler there finds a waterfall and quickly sets about

clearing the land around it and building a mill on the site. By the

application of his labor, this person has acquired this land as their

private property. But, in so doing, they now inherently prevent everyone

else from having the opportunity to make use of that property. If there is

only one waterfall in the area, then only one mill can be built. So the

waterfall and the mill are now owned by this one individual, and that

individual now decides to not perform any more labor, but instead hires

people to work at the mill.

What now of Locke's statement that property is defined by the application

of an individual's labor? Now the owner of the mill no longer performs

labor, and all of the labor is being performed by other people who don't own

the property they are applying their labor to. They are working at the mill,

producing grain, but they don't own the mill or the grain, and thus end up

not owning any of the product of their labor. In capitalist systems,

property ownership trumps labor, such that the lineage of ownership descends

from property ownership, not from labor. We agree that people should be able

to keep the fruits of their own labor, but as soon as private property is

established, it then prevents others from being able to keep the fruits of

their own labor. People can only keep the fruits of their own labor when

they labor upon "common property" or upon their own property. When anyone labors upon

someone else's "private

property", they inherently cannot keep the fruits of their own labor. The

fact that people choose to work at the mill is a de-facto result of the

monopolization of resources inherent in the creation of private property.

Because the mill may be the most efficient means of creating value in the

community, the opportunity cost of working at the mill becomes more

advantageous than working independently on less efficient property. What

this does is create "voluntary" exploitation.

This is because keeping 100% of what your labor produces as an individual

working inefficiently can be less advantageous than keeping less than the

full value of what you produce working more efficiently. Thus, the creation of

efficient value generating property effectively forces individuals into

exploitation. Consider that in the community there are no other places to

build a water driven mill. Imagine that the only thing to be done is create

grain. An individual can either make their own mill that is powered by,

say, horses or their own human power, or they can work at the water

mill. Let's say that they make their own mill driven by horses, and that

they are able to produce $500 worth of grain a week using their own mill,

but if they were to work at the water driven mill they could get paid $700 a

week. However, though they would be getting paid $700 a week, more than they

could earn on their own, they would actually be producing $2,000 worth of

grain a week. So, they can make $2,000 worth of grain at the water mill

owned by someone else, and keep $700 of it, or they can make $500 worth of

grain on their own and keep 100% of it. Because the next best alternative is

still worse than exploitation, this drives the voluntary exploitation.

This situation exists because of private property rights, but it is a

paradoxical situation, because not allowing individuals to establish private

capital is problematic as well. The reason that this economic issue has been

so contentious and hard to address for so long is because it is a paradox

that's hard to deal with. This isn't an easy problem to solve.

It is clear that today in all modern societies there is not a large

reserve of common property from which individuals can acquire private

property simply by the application of their labor, as was the case in early

America. Today most property is already private property, and thus, Locke's

principles of private property ownership are violated due to his caveat that

the creation of private property is only legitimate when there is enough

left in common for others, i.e. when everyone is capable of acquiring

private property merely by the application of their labor. That clearly is

not true today because the vast majority of people in all modern economies

exercise their labor upon property which is owned by other people.

So what can be done about this? Well, this situation was addressed in

1795 by Thomas Paine, a leading voice of the American Revolution.

In 1795 Thomas Paine published a tract titled

Agrarian Justice, in which he proposed the creation of a guaranteed

income system, to be paid equally to all people, funded effectively by a

tax levied on all land owners. What is most important about Paine's proposal

was his justification for it. In Agrarian Justice he states:

Poverty, therefore, is a thing created by that which is called

civilized life. It exists not in the natural state. On the other hand,

the natural state is without those advantages which flow from

agriculture, arts, science and manufactures.

Civilization, therefore, or that which is so-called, has operated two

ways: to make one part of society more affluent, and the other more

wretched, than would have been the lot of either in a natural state.

...

It is a position not to be controverted that the earth, in its

natural, [un]cultivated state was, and ever would have continued to be, the

common property of the human race. In that state every man would have

been born to property. He would have been a joint life proprietor with

rest in the property of the soil, and in all its natural productions,

vegetable and animal.

But the earth in its natural state, as before said, is capable of

supporting but a small number of inhabitants compared with what it is

capable of doing in a cultivated state. And as it is impossible to

separate the improvement made by cultivation from the earth itself, upon

which that improvement is made, the idea of landed property arose from

that parable connection; but it is nevertheless true, that it is the

value of the improvement, only, and not the earth itself, that is

individual property.

Every proprietor, therefore, of cultivated lands, owes to the

community ground-rent (for I know of no better term to express the idea)

for the land which he holds; and it is from this ground-rent that the

fund prod in this plan is to issue.

...

Nothing could be more unjust than agrarian law in a country improved

by cultivation; for though every man, as an inhabitant of the earth, is

a joint proprietor of it in its natural state, it does not follow that

he is a joint proprietor of cultivated earth. The additional value made

by cultivation, after the system was admitted, became the property of

those who did it, or who inherited it from them, or who purchased it. It

had originally no owner. While, therefore, I advocate the right, and

interest myself in the hard case of all those who have been thrown out

of their natural inheritance by the introduction of the system of landed

property, I equally defend the right of the possessor to the part which

is his.

Cultivation is at least one of the greatest natural improvements ever

made by human invention. It has given to created earth a tenfold value.

But the landed monopoly that began with it has produced the greatest

evil. It has dispossessed more than half the inhabitants of every nation

of their natural inheritance, without providing for them, as ought to

have been done, an indemnification for that loss, and has thereby

created a species of poverty and wretchedness that did not exist before.

In advocating the case of the persons thus dispossessed, it is a

right, and not a charity, that I am pleading for. But it is that

kind of right which, being neglected at first, could not be brought

forward afterwards till heaven had opened the way by a revolution in the

system of government. Let us then do honor to revolutions by justice,

and give currency to their principles by blessings.

Having thus in a few words, opened the merits of the case, I shall

now proceed to the plan I have to propose, which is[:]

To create a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every

person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen

pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her

natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed

property. And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to

every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as

they shall arrive at that age.

...

I have already established the principle, namely, that the earth,

in its natural uncultivated state was, and ever would have continued to

be, the common property of the human race; that in that state, every

person would have been born to property; and that the system of

landed property, by its inseparable connection with cultivation, and

with what is called civilized life, has absorbed the property of all

those whom it dispossessed, without providing, as ought to have been

done, an indemnification for that loss.

The fault, however, is not in the present possessors. No complaint is

tended, or ought to be alleged against them, unless they adopt the crime

by opposing justice. The fault is in the system, and it has stolen

perceptibly upon the world, aided afterwards by the agrarian law of the

sword. But the fault can be made to reform itself by successive

generations; and without diminishing or deranging the property of any of

present possessors, the operation of the fund can yet commence, and in

full activity, the first year of its establishment, or soon after, as I

shall show.

It is proposed that the payments, as already stated, be made to every

person, rich or poor. It is best to make it so, to prevent invidious

distinctions. It is also right it should be so, because it is in lieu of

the natural inheritance, which, as a right, belongs to every man, over

and above property he may have created, or inherited from those who did.

What Paine is basically saying is that in the "natural state", prior to

the establishment of property rights, everyone had equal access to the land.

The establishment of property rights then inherently dispossessed some

people without any compensation. And now, people are born into a system in

which they are dispossessed, in which they are essentially born with less

access to property than if civilization didn't exist at all. Thus, Paine

argues, such people have a right to the value which has been taken away from

them, i.e. that we all have a natural right to use of the land, since the

land was not create by anyone, but being born into a system where all land

is already owned by others inherently deprives people of this natural right.

Thus, people born into such a system are owed compensation for this loss. Viewed as such, this compensation is a right, not a charity,

because this is compensation for something that has been taken away from

them.

Paine then goes on to say that the best way to implement such a system is

simply to make equal payments to everyone, so as to avoid complication and

bickering.

Paine's case obviously applies specifically to land, but the principles

can be more broadly applied. In essence, the creation of all capital is a

double-edged sword. On the one hand development of capital increases overall

productivity and can lead to net improvements in quality of life. On the

other hand, development of capital can, and often does, displace workers and

decrease the value of some individuals' labor. People deserve compensation

for these losses, because the ability to profit from their own labor is

being taken away from them. I argue that people have a natural right to the

value of their own labor, and that people therefore deserve an indemnification

for the loss of their labor value due to the development of capital. This

indemnification should come in the form of capital ownership.

We can now turn to Thomas Jefferson, one of the most influential and

important Founding Fathers. Jefferson was a strong advocate of democracy and

distribution of political power. In fact

Jeffersonian-Democracy is described as highly egalitarian system where

political and economic power is securely in the hands of the "common

people". This egalitarian ideal was pervasive in all of Jefferson's ideas

about government, economics, and domestic policy. Jefferson knew that

egalitarian democracy required highly distributed ownership of capital. This

is why Jefferson was an advocate of family farming and opposed to the

development of large scale manufacturing and corporations.

I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries; as

long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there

shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get piled upon

one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become corrupt as

in Europe.

-

Letter to James Madison, December 10, 1787

It ends, as might have been expected, in the ruin of its people, but

this ruin will fall heaviest, as it ought to fall on that hereditary

aristocracy which has for generations been preparing the catastrophe. I

hope we shall take warning from the example and crush in it’s birth the

aristocracy of our monied corporations which dare already to challenge

our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of

our country.

-

Letter to George Morgan, November 12, 1816

The property of [France] is absolutely concentered in a very few

hands, having revenues of from half a million of guineas a year

downwards. ... But after all these comes the most numerous of all the

classes, that is, the poor who cannot find work. I asked myself what

could be the reason that so many should be permitted to beg who are

willing to work, in a country where there is a very considerable

proportion of uncultivated lands? ... It should seem then that it must

be because of the enormous wealth of the proprietors which places them

above attention to the increase of their revenues by permitting these

lands to be laboured. ... Another means of silently lessening the

inequality of property is to exempt all from taxation below a certain

point, and to tax the higher portions of property in geometrical

progression as they rise. Whenever there is in any country, uncultivated

lands and unemployed poor, it is clear that the laws of property have

been so far extended as to violate natural right. The earth is given as

a common stock for man to labour and live on. If, for the encouragement

of industry we allow it to be appropriated, we must take care that other

employment be furnished to those excluded from the appropriation. If we

do not the fundamental right to labour the earth returns to the

unemployed. It is too soon yet in our country to say that every man who

cannot find employment but who can find uncultivated land, shall be at

liberty to cultivate it, paying a moderate rent. But it is not too soon

to provide by every possible means that as few as possible shall be

without a little portion of land. The small landholders are the most

precious part of a state.

-

Letter to James Madison, October, 1785

The reason that Jefferson associated farming with democracy was that it

was relatively easy to ensure an egalitarian distribution of property in the

form of land in America, and family farmers, by owning their own capital, worked for

themselves. Jefferson opposed cities and corporations, because he knew that

in cities many people were unable to own their own capital and work for

themselves. Jefferson believed that under such circumstances workers

would become dependent upon corporations and employers and lose their

political independence. Jefferson was deeply opposed to hierarchical

systems, which was why he opposed both corporations and a strong central

government, believing that a strong central government would end up

primarily serving the interests of a wealthy aristocracy.

However, Jefferson ultimately knew that America couldn't remain an

agricultural society forever and that eventually the land would run out and

it would no longer be possible for everyone to be a farmer. However, he

never really addressed how to deal with this fact, he merely hoped that the

industrialization and urbanization of America would be held off as long as

possible. Jefferson understood how to distribute political and economic

power within an agricultural framework, but there was no model for

distributed political and economic power within an industrial framework. As

far as Jefferson was concerned, the development of industry and banking

would inevitably lead to the development of economic inequality,

aristocracy, and plutocracy. On the other hand, Jefferson was no

"conservative" either. He was a liberal in the true sense, and was a strong

advocate of a liberal public education and technological modernization.

Jefferson hoped that science and technology could be developed in ways to

make home-based manufacturing and modernization possible. Jefferson

basically envisioned a nation where everyone owned their own land and was

highly self-sufficient, with home-based production of commodities using

machines so that automation and mechanization would enable individuals to

remain independent from corporations and centralized industry. As we know,

this is not at all how things turned out.

But ultimately, Jefferson's key concept was that democracy was inherently

dependent upon highly distributed capital ownership. In Jefferson's mind,

that meant an agricultural economy where land was relatively equally divided

up among everyone. What is obvious today is that this isn't possible. Modern

society can't exist within the framework of a family farming nation. But,

the reason that Paine, Jefferson and may others of their time focused on

land distribution was because at that time land was far and away the most

important form of capital and wealth. Today that is no longer the case.

Jefferson's core concepts were essentially correct. Democracy is

dependent upon highly distributed capital ownership. Corporations and

banking do inherently lead to the development of hierarchical systems that

both create economic inequality and undermine democracy. The challenge then

is, how do we have both a modern industrial economy and highly distributed

capital ownership? In Jefferson's mind that required direct ownership of

actual physical capital in the form of land. The reason that Jefferson's

vision failed is that it was dependent upon distributed land ownership, but

there was no mechanism in place to ensure continued distribution of capital

ownership as freely available land inevitably disappeared and land became

less important after the industrial revolution. Thus, we have to do the best

that we can given the requirements of a modern economy, and that means

distributing ownership of corporations and financial instruments via shares.

National Individual Investment Program vs. Universal Basic Income

There has been growing interest in the use of a

universal

basic income (UBI) as a means of addressing economic inequality and

poverty in developed economies; see examples

here and

here. Advocates of a universal basic income see it as a way to address

rising income inequality and alleviate poverty.

A universal basic income could address both poverty and income

inequality, but in my option something like the National Individual

Investment Program (NIIP) I am proposing has several significant advantages

over a universal basic income.

I think the most important advantage of the NIIP over a UBI is the fact

that the NIIP would actually re-distribute capital, and thus truly alter

before tax income distributions as well as truly altering the distribution

of political power in society.

A UBI does not do these things. Ultimately, a UBI becomes an allowance

provided by the rich. As such, it suffers the same long-term problems as

many of the New Deal era economic reforms. It can only exist at the whim of

the wealthy, who, through their retained ownership of capital, would still

have the political, social, cultural, and economic power to undermine the

program. Even if such a program were to be implemented, it's long-term

maintenance would be forever in peril, in much the same way that Social

Security is today, except it would be much worse, because it would be

impossible to implement a UBI without raising significant taxes on the rich,

unlike Social Security, which basically doesn't tax the rich at all.

Another advantage of the NIIP is that it can be supported and be

meaningful with a much lower tax rate. It is basically a much more

affordable approach than trying to provide a basic cash income. Most

estimates for a UBI program in the United States today agree that such a

program would need to provide about $10,000 a year to every adult.

To reach this $10,000 level would essentially require about a 10% tax on

all income, with no exemptions. This would be unaffordable currently, but

some advocates for a UBI propose supporting the program by cutting existing

programs, such as food stamps, housing assistance, and even Medicaid and

Social Security.

In such cases, a UBI could actually leave many people worse off than they

are today, or at best their position would be little changed. In this case,

a UBI wouldn't really do much of anything to address income inequality or

alleviate poverty, it would just be a means of consolidating many different

income assistance programs into a single program. This would certainly

reduce the administrative costs of income assistance, but such proposals

aren't really about fundamentally changing the economic and social dynamic.

Because the NIIP that I propose does not give people cash, but instead

provides people with an investment, it can actually provide more economic

security at a lower cost. That's what makes it more affordable. Funding a

UBI requires funding the full benefit with taxation, but with the NIIP, much

of the benefit would come from appreciation of the assets over time as well

as dividends, so those are benefits that don't have to come from taxation.

In addition, because it's an investment most people would very likely

leave at least some of the benefit in "savings", i.e. in their account,

without cashing it out as soon as possible and spending it. This means that

as a financial buffer, or safety net, it would almost certainly provide much

stronger financial protection. It would not be difficult for an individual

to amass $20,000 - $50,000 in NIIP assets by age 30 even while selling

off some assets from time to time. If they then have

a major financial emergency they would have those resources to draw on. One

can argue that if people took the money from their UBI payments and invested

them then it would be the same, which is essentially true, but since those

benefits come in the form of cash they would be much more likely to just

spend it, especially if it replaced existing poverty assistance programs,

and it would also require more investment savvy from the public.

But again, the most important difference between the two types of

programs is that the NIIP is designed to actually re-distribute capital

ownership. Doing this actually enfranchises people, whereas a UBI does not.

The NIIP creates a sense of ownership and I think would be viewed much

differently than a UBI. A UBI would be seen as charity provided by the

rich, whereas the NIIP would be seen as earned.

A UBI is a mechanism for again trying to treat the consequences of

concentrated capital ownership while doing nothing to actually change the

concentration of capital ownership. The NIIP is a mechanism to directly

address the concentration of capital ownership, recognizing that

concentrated capital ownership is the root cause of economic inequality in

the first place. The NIIP would be much more affordable, while likely having

much more far reaching effects on the economy and society than a UBI.

Conclusion and Summary

The primary root cause of extreme economic inequality in America and

other capitalist countries is concentration of capital ownership. This

concentration of capital ownership is an inherent product of capitalism and

has in some ways been exacerbated by government policies that cater to the

interests of the wealthy and business owners. Unfortunately this has often

led to an adversarial relationship between labor and capital, whereby the

interests of workers are pitted against the interests of capital owners.

When a small portion of the population owns and controls the majority of the

capital and the majority of the population has no meaningful capital wealth

or income, then this type of adversarial relationship is inevitable, because

in fact the interests of capital owners are in opposition to the interests

of wage-laborers.

Historically the conflict of interests between capital owners and

wage-laborers has been addressed in capitalist countries by trying to either

increase the share of revenue that is paid to wage-laborers or to use

redistributive taxation to address the most basic needs of non-capital

owners through government programs, such as food and housing assistance. The

problem with these approaches is that they fail to actually enfranchise the

working class and they in fact actually facilitate further concentration of

capital ownership. Another problem with this approach is that it is in

conflict with the efficient development of capital. It leads to the

all-too-common refrain that we hear today of calls for "job creation". But

the objective of an economy is not to create jobs, it is to create wealth.

Jobs are merely a means to that end, they are not the goal in and of itself.

The problem is that for the vast majority of the population wages, i.e.

jobs, are the only means of distributing income. What people really needed

however, is not a "job", but rather an income. No one needs a job, but

everyone needs an income. What we have is a system where the incomes of the

vast majority of the population are dependent upon wages, i.e. holding a

job, and the incomes of a small minority of the population are a product of

capital ownership.

The solution to this problem is not to try and increase the portion of

revenues going to wages, but rather to increase the distribution of capital

income, so that increases in capital development and capital income benefit

everyone and everyone can become less dependent on wages, just as the

wealthy are today. The problem with the current American economy is that it

is too "job bound". The economy is too dependent on jobs as a mechanism for

income distribution, despite the fact that a growing share of income is

actually going to capital. The income distribution mechanism is out of sync

with the mechanisms of creating wealth. Wealth is increasingly created by

machines, not human labor, but a shrinking share of the population owns and

controls the machines that create the wealth. Yet, it is a fact that the

wealth of the capital owners is only made possible by the labor and

existence of non-capital owners.

The solution clearly is more broadly shared capital ownership. It is an

obvious solution that has been known for a long time. That's what the

communist and socialist movements of the 19th and 20th century were all

about, but the National Individual Investment Program is a different

approach, that is actually much simpler and in line with American society

and traditions. The communist and socialist movements essentially sought to

abolish private capital ownership, but the National Individual Investment

Program seeks merely to make everyone meaningful private capital owners.

It is not a silver bullet. It won't solve all of the problems of economic

inequality, and the program as I have proposed it certainly won't put an end

to poverty, but that's actually the beauty of it. What I'm proposing isn't

actually that radical; in fact it's not very different from some

conservative proposals for the privatization of Social Security. What I'm

proposing is an independent program, that can be implemented all by itself.

It doesn't require any radical transformation of the economy or

restructuring of other programs or an overhaul of the tax code, etc. Many of

those things would be nice, and a lot could be done to improve the economy

and make it more fair through a wide variety of economic and public policy

reforms. The key is that a program like the National Individual Investment

Program isn't dependent on any of that taking place. It doesn't require a

revolution; it doesn't require re-envisioning the economy from the ground

up.

Once implemented, the program could easily evolve over time through

adjustments to the level of the tax that funds the program and adjustments

to the number of hours worked to receive full time benefits. If and when an

increasing share of national incomes goes to capital and demand for human

labor decreases, the number of working hours required to receive full time

benefits can be reduced, allowing for increased capital income as demand for

labor declines.

Furthermore, the implementation of a program like the one I am proposing

here would, I believe, make other economic reforms more likely to happen in

the future, because a result of this program would be greater economic

enfranchisement of the majority of the population and a decrease in the

concentration of capital ownership. It would, as Thomas Jefferson understood

long ago, strengthen democracy by distributing political power via the

distribution of capital ownership. As Jefferson understood, ownership is a

major source of political power and when ownership is highly distributed so

is political power. When ownership is concentrated so is political power. Thus,

the first and most important mechanism for fostering democracy is

distributing ownership of capital. That is exactly how and why American

democracy was established in the first place, via the widespread

distribution of capital ownership in the form of land. In this sense, the

National Individual Investment Program is merely a 21st century version of

the land distribution policies of early America, and nothing could be more

American than that.

|